Are President Trump and Jerome Powell acting as if the United States is already in a recession?

At the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, the US government approved record spending bills totaling $5 trillion in an attempt to keep businesses afloat, employees, and the economy from sliding into recession. Five years later, somehow, the US economy has not only avoided contraction, but managed to grow, an outcome that many investors thought was impossible.

By 2025, the White House announced another major round of stimulus in the form of President Trump’s big, beautiful bill. Projections from the nonpartisan organizations the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) put the cost of the law — the additional burden on the national debt — at about $3.4 trillion.

While most economists agree that revenues from tariffs will offset the majority of this spending, the fact remains that a massive amount of stimulus is being pumped into the economy at a time when it is already not only stable, but growing.

More stimulus is expected in the form of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve. Although inflation remains at around 3% — above the Fed’s 2% target — voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee have signaled their openness to multiple cuts, with Trump appointee Stephen Meir even calling for a 50 basis point cut before the end of the year.

This begs the question of why Washington, between the central bank and the White House, is acting as if the United States is in a recession — or at least preparing for one.

The Fed’s cuts could come for a variety of reasons: The central bank may genuinely believe that its monetary policy, which is 100 basis points above inflation, is too restrictive. Or perhaps its board members are vying for Trump’s attention to replace Chairman Powell next year. Or perhaps you see weakness in economic data, which you are trying to anticipate.

Citadel CEO Ken Griffin has I have already raised this issue. Speaking at a conference in New York earlier this month, Griffin said Trump 2.0 policies had created a “huge rally” in markets thanks to their pro-growth agenda. Even then, he warned, more stimulus measures may be more conducive to a recession than “a period of nearly full employment a few years into the business cycle.”

Does Washington know something we don’t know?

Washington policy – from the central bank or the White House – may make more sense if America is in a recession. According to Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s, this is already the case for more than half of the states in the United States. In a recent note, Zandi found that the economies of 23 US states are shrinking, only 16 states are experiencing economic growth, and 12 states are classified as “running waters.”

Zandi previously said luck That many people’s consumer sentiment is in line with a recession, except for the fact that they currently have jobs: “The way people are looking at their economy, their finances, is pretty consistent with a recession — the difference here is they’re not losing their jobs. And yet, we’re at 4.3% unemployment… and even in a recession, we got 5% or 5.5%, so we’re talking about a percentage point… not There are a lot of people. You could argue that this is not a very good litmus test to see if you are in a recession or not.

But Zandi said luck In an exclusive interview, the White House is certainly not charting its course based on that concern: The goal of OBBA, he believes, is to create enough positive sentiment to push the administration through next year’s midterm elections.

But the Fed is another story: “The Fed is putting more weight on growth and jobs. They’ve seen the labor market moving sideways… Unemployment is low, but it’s rising, especially among young people, and I think that’s critical. They’re weighing on inflation risks because inflation expectations are still anchored, and (the Fed) feels that the increase in inflation (by) tariffs will be “More one-time, less ongoing.”

Zandi adds that the Fed is “rightfully” concerned about its independence. “I think they desperately want to avoid a recession because if it happens they will be blamed and their independence will be more seriously threatened as a result. So I think they are calculating that it is better to err on the side of supporting growth, let alone worrying about future inflation.”

On the other end of the spectrum, says David Doyle, chief economist at Macquarie luck While Washington is not necessarily shaping its policy due to fears of an impending recession, policymakers will be keen to maintain growth. He warned that this was a fine balance to maintain, one that might tend to overstimulate the economy: “If they succeed — the Fed and the administration jointly succeed and avoid a recession — in 2026, then maybe the risk is in the other direction: Is there overactivity?”

Doyle added that there is a “good chance” people will start talking about raising interest rates from the Fed next year. “Inflation appears to have been on a steady downward path, and now appears to be stabilizing at around 3%. If we see the labor market rebound, and perhaps more tariff rates go through…inflation will be even higher in 2026.”

Is the current policy appropriate?

While Washington’s policy may avert disaster in the near term, the question remains whether it is appropriate to approve such a massive stimulus during a relatively stable period of the economic cycle, especially in light of the recent government. The shutdown (which occurred specifically because of a debate in Congress over spending).

The 2025 shutdown happened because Democrats want to see extensions of tax breaks and continued spending on health agencies, both of which come directly from federal government funds. While Republicans oppose these expenditures, they were willing to extend and approve tax cuts that would cut federal revenues by as much as $4.5 trillion, according to calculations by the Bipartisan Policy Center.

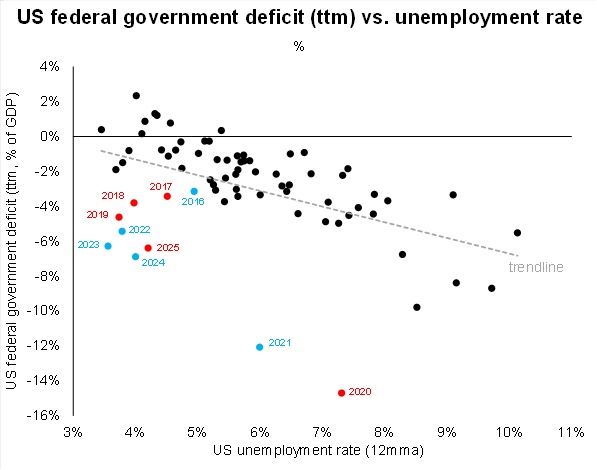

In theory, governments should run larger deficits during periods of high unemployment: they spend more money to stimulate the economy while taking less tax revenue from exploited workers. Budgets should be more balanced when economic times are good, when there is less need for government stimulus and greater opportunities to grow tax revenues.

With the national debt now approaching $38 trillion, Macquarie’s research found that since 2018, governments (regardless of party) have added to deficits at levels greater than the historical average under similar economic conditions. By plotting the US unemployment rate against the federal deficit as a share of GDP, Macquarie found that an unemployment rate of about 5% historically would result in a 1% change in the deficit. This correlation, which was prevalent before 2018, follows a steady decline with rising unemployment rates, as an unemployment rate of 8% led to a change in the deficit of -4%.

This correlation shifted in 2018, indicating that macroeconomic conditions and federal budgets were becoming increasingly decoupled. For example, a relatively stable unemployment rate of 4% in 2019 still saw a deficit shift of -4%, while a similar unemployment level in 2024 saw a further decline of -6%.

“The main takeaway I tell our clients on this is: Normally when unemployment is 4%, the deficit is going to be like -1% or even (can you believe it?) a balanced budget. Now we’re in a system where it’s like -6, -7%, and that’s a broader structural deficit. That’s a problem, and what it means is that if we get into a recession and unemployment, let’s say it explodes to 7% or something like that, you’ll probably “About a 12% deficit,” Doyle added.

“How will the United States finance its long-term obligations and how will it finance its deficit in this situation?” Doyle asks.

The point at which investors begin to question the viability of debt is not Simply down to the amount of debt (After all, government borrowing provides the basis for the bond market that forms one of the pillars of the global economy.) But whether the country has the ability to repay or service its debt, or whether it will resort to quantitative easing to balance the books and dilute the value of the investment, remains to be seen. That’s why economists are concerned with a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio, determining whether the country is growing enough to justify its borrowing, which is expected to rise to 156% by 2055. According to the Central Bank of Oman.

Zandi said that if it is estimated that the current fiscal package not only covers its costs but also grows the economy, then the path is justified. “With the big, beautiful bill, you get some stimulus: it’s already stimulus and it adds some stimulus, so from that perspective, it’s not unprecedented,” he added.

Whether the US economy is stimulating or not, it has a mountain to climb before Washington’s debts align more appropriately with its economic context. “The amount of support for the economy that has been in place since the pandemic, we have never seen anything like this before,” Zandi added. “The primary deficit should be at zero, and it should be in surplus, when you are at full employment.”

Zandi noted that even a “modest and relatively small” stimulus would likely heighten concerns about debt. “We already have this massive deficit and debt and we’re not doing anything about it — quite the opposite. So it’s unprecedented in that sense.”

Post Comment