‘Bermuda Triangle of Talent’: 27-year-old Oxford graduate turns down McKinsey and Morgan Stanley to find out why the smartest Gen Zers keep selling

The Vice-Chancellor stood on the podium at the Sheldonian Theater in Oxford, her voice echoing off the carved ceiling: Now go out there and change the world. The rustle of robes. The cameras clicked. Rows of classmates smiled, clutching the steps that would soon connect them MackenzieGoldman Sachs and Clifford Chance: the holy trinity of elite exit plans.

Simon van Teutem also applauded, but for him, the ridicule was unbearable.

“I knew where everyone was going,” he said in an interview. luck. “Everyone did it. Which made it worse — we were all pretending not to see it.”

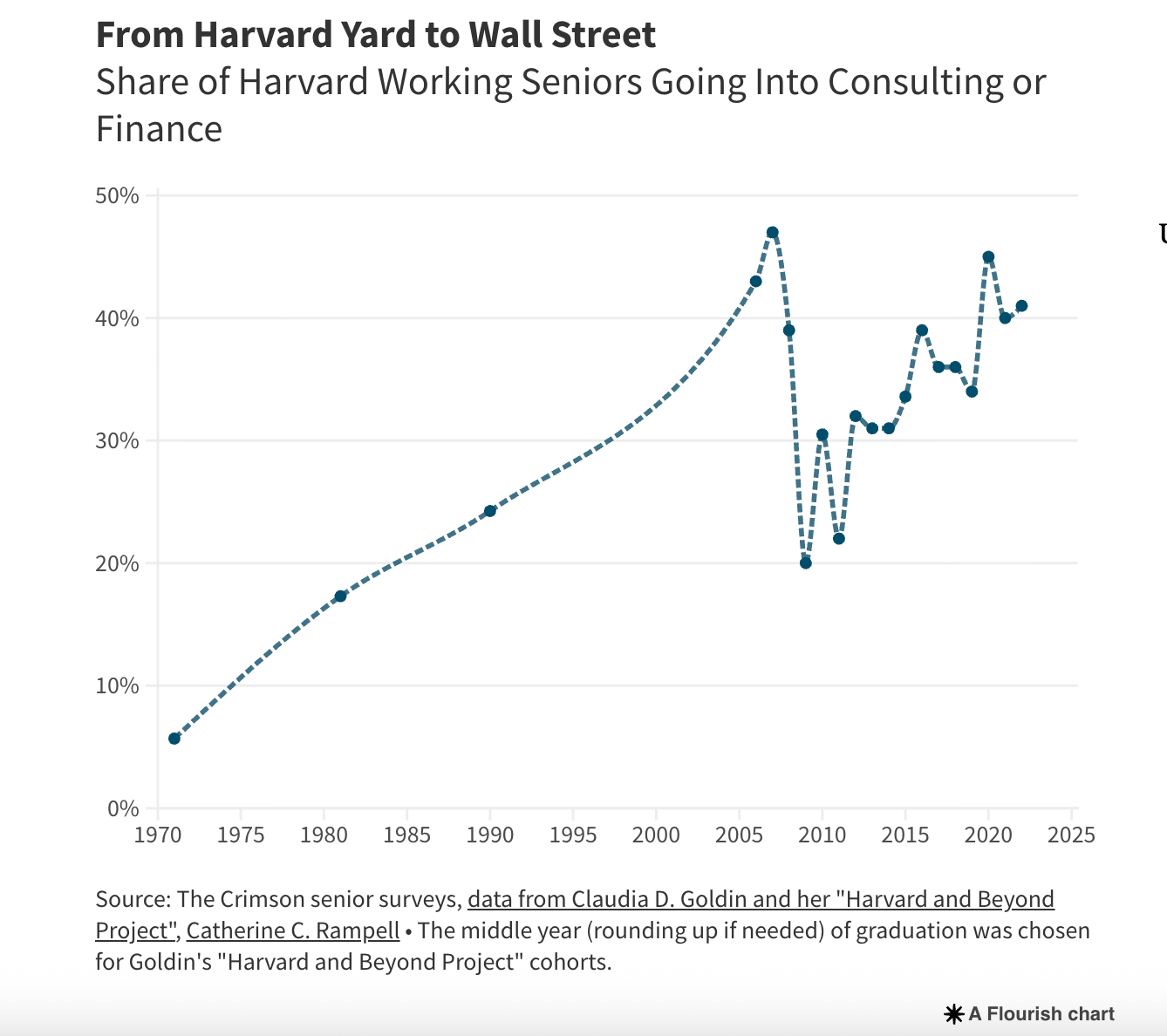

Elite career paths have actually consolidated over the past half-century. In the seventies, One in twenty graduates from Harvard He went into careers like finance or consulting. Twenty years later, that number had jumped to one in four. last year, Half of Harvard graduates Get jobs in finance, consulting, or big technology companies. Salaries rose similarly: data from exits of senior employees reconnaissance For the Class of 2024, 40% of employed graduates earned first-year salaries exceeding $110,000, and among those who entered consulting or investment banking, nearly three-quarters exceeded that threshold.

Months after this party, Van Teutem received two such offers: a job at McKinsey or… Morgan Stanley. Instead, when he was 22, he declined both and spent three years working for the Dutch media. Who correspondsR Writing a book about the hidden gravity that makes such decisions seem inevitable.

Van Teutem took on the project after watching the prestigious treadmill lure talented and creative kids into trivial chores, then close the door behind them. He noted that everyone always says they are doing their banking just to get their foot in the door, but they always end up staying.

“These companies have cracked the psychological code of insecure overachievers and have built a self-reinforcing system,” Van Teutem said.

Bermuda Triangle of Talent

the book,, Bermuda Triangle of Talentarose from personal frustration. A longtime geek who was fascinated by economics and politics, he arrived at Oxford as an undergraduate in 2018 determined, as he put it, to “do something good with my talents and privileges.”

Within two years, he was training in BNP Paribas And then Morgan Stanley, who slept at his desk working on mergers and acquisitions with the intensity of “rescuing children from a burning house.”

His annoyance wasn’t about the business itself; he’s not from Generation Z who believes all companies are “evil,” he insisted. “I thought the work was somehow trivial or mundane.”

At McKinsey, where he next interned, the work seemed more polished but no less hollow.

“I was surrounded by rocket scientists who could build really cool things, but they were building simple Excel models or reverse engineering to get to the conclusions we actually wanted,” he said.

He turned down full-time offers and instead began interviewing people who didn’t make it. Over the course of three years, he spoke to 212 bankers, consultants and corporate lawyers – from trainees to partners – to understand how so many high-achieving graduates drift into jobs they secretly hate. He concluded that the harm was not villainy, or even greed, but rather loss of potential: “The real harm lies in the opportunity cost.”

He found that money was not the magnet, at least not at first.

“In the initial draw, most elite graduates don’t make the decision based on salary,” he said. “It is the illusion of infinite choice and social status.”

At Oxford, this delusion was everywhere. Banks and consulting companies dominated job fairs; Governments and NGOs emerged as afterthoughts. He remembers his first encounter with the system: BNP Paribas hosted a dinner party for “outstanding students” at an upscale Oxford restaurant. He applied because he was broke and wanted a free meal, and he ended up interning there.

“It’s a game we’ve been trained to play,” he said. “You’re wired that way. You’re always looking for the next level, Harvard after Harvard, Oxford after Oxford.”

By the time many graduates realize that there is no gold star at the end—that the next level is simply higher pay and a longer chipset—it is already too late. Most people think they can leave the corporate world after two or three years to pursue their dreams, but very few actually do.

“At least I can buy a house for my children.”

He tells the story of “Hunter McCoy,” a pseudonym for a man who one day wanted to work in politics or at a think tank, to illustrate this point. McCoy envisioned a future career in advocacy. Fresh out of college, McCoy joined a law firm and told himself he would stay for two, maybe three years, long enough to pay off his student loans. He even had a name for the finish line: Him “fk your number.” This was the amount that would give him the freedom to pursue political work.

But freedom turned out to be a moving target. Living in an expensive city, surrounded by colleagues who billed a hundred hours a week and hailing cabs home at midnight, McCoy was always the poorest man in the room. Every bonus, every new title, pushed his number a little higher.

The trap was slowly tightened. First came the mortgage, then the renovations, then the quiet creep of what used to be Named “Lifestyle inflation.” You buy a nice apartment and want a good kitchen. If you buy a kitchen, you’ll want a knife set that matches it. Every new convenience requires another upgrade, another night at the office to keep everything the same.

“High income stimulates high expenses,” Van Teutem said. “High expenses beget more high expenses.”

By his mid-forties, McCoy was still working at the same company, and was still telling himself he would be leaving soon. But the years calcified into guilt.

“Because I never saw my kids, because I always worked so hard, I told myself no, I want to keep going for a few more years,” McCoy told Fan Teotiem. “Because at least I will be able to buy a house for my children instead of losing so much.”

The saddest part, he said, is McCoy’s uncertainty about what will remain if he leaves.

“He told me he wasn’t sure his wife would stay with him,” Van Teutem said quietly. “This was the life I signed up for.”

The confession struck him as so crude and tragic, a glimpse into how ambition hardens in captivity.

“It made me glad I didn’t go through it,” he said. “Because you think you can trust yourself with these decisions. But you may not be the same person three years later.”

The long shadow of Reagan, Thatcher and the Big Three

However, what Van Teutem describes is part of a system-wide phenomenon that has been going on for decades.

This tremendous growth Researchers So-called “career switching”, where students narrow down to only two or three industries considered socially prestigious enough to work in, goes hand in hand with the financial transformation and deregulation that Western economies took in the second half of the 20th century. The neoliberal revolution, led by former President Ronald Reagan in the United States and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, succeeded in expanding capital markets sufficiently to create entirely new industries of manipulation of financial instruments; thus, The explosion of the finance industry. At the same time, governments and companies began to outsource expertise to private companies under the banner of market efficiency, giving birth to the modern consulting industry. (The last of today’s “big three” consulting firms was… Recently established AS 1973.)

As these companies captured a larger share of the country’s profits, they became synonymous with meritocracy itself: exclusive, data-driven, and ostensibly apolitical. They have provided graduates with not only jobs, but also a sense of belonging and identity.

There’s another, quieter trap here, too: the cost of living in big cities has never been higher. In cities like New York and London – the centers of global finance’s gravity – comfortable living has become a luxury good. Smart assets 2025 He studies It found that a single adult in New York now needs about $136,000 a year to live comfortably. In London, a single person needs around £3,000 to £3,500 a month just to cover basic living expenses, transport and accommodation. Financial advisors say now A salary of £60,000 only buys relative comfort – the ability to save and not live paycheck to paycheck – an amount that only 4% of British graduates do. We expect to do Leaving the university.

How many early career jobs pay more than $136,000, or £60,000 a year? If a 22-year-old comes out of college with a natural desire to explore the big city, that’s normal friends or sex in the city, But they do not have a cushion of parental support, they must be within a narrow range of roles that cross the threshold. This means that many careers begin merely by pursuing a salary level rather than pursuing task-oriented work.

Incentivize risk-taking

Van Teutem believes the solution lies not so much in moral awakening as in determination.

“You can guide organizations towards change or towards risk,” he said. His favorite example is Y consolidated, He pointed to the Silicon Valley accelerator, which since its founding in 2004 has succeeded in turning a few dozen idea geeks into companies now worth about $800 billion – “more than the Belgian economy.”

YC succeeded because it lowered the cost of risk: small checks, quick reactions, and a culture that made failure survivable.

“In Europe, we are doing a very bad job of this,” he added.

He believes that governments can do the same. In the 1980s, Singapore began competing directly with companies for top graduates, offering them early job offers and eventually tying the salaries of senior civil servants to those of the private sector. It’s controversial, sure, but she’s built a country that can retain its best talent.

The nonprofit world has learned similar lessons. Teaching first In the United Kingdom and Teach for America Mimicking consulting firms’ recruiting methods—selective cohorts, “leadership program” branding, and quick bucks—to lure elite students into classrooms rather than boardrooms.

“They are using the same tricks as McKinsey and Morgan Stanley, not as a charity, but as a stepping stone,” Van Teutem said.

Financial pressures continue to distort those choices. In the United States, Unemployment is rising among recent university graduates With the slowdown in the labor market.

He hopes universities and employers will emulate the YC model: lower the downside, raise the prestige of the attempt.

“We have made risk a privilege,” he said. “This is the real problem.”

Post Comment