Officials at a Syrian prison for IS suspects say attacks by the group are on the rise

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBCIn the complex mosaic of the new Syria, an old battle against a group calling itself the Islamic State (IS) continues in the Kurdish-controlled northeast. It’s a conflict that has slipped from the headlines – along with larger wars elsewhere.

But Kurdish counter-terrorism officials told the BBC that IS cells in Syria were regrouping and stepping up their attacks.

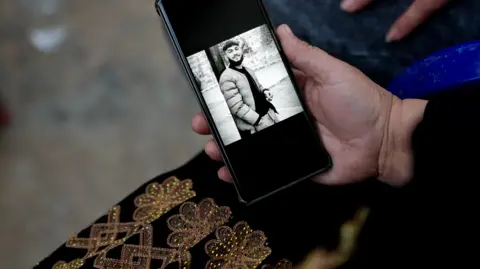

Walid Abdul-Basit Sheikh Moussa is obsessed with motorcycles and finally managed to buy one in January.

The 21-year-old only got a few weeks to enjoy it. He was killed in February while fighting against IS in northeastern Syria.

Walid was so eager to fight the militants that he ran away from home at the age of 15 to join the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They brought him back because he was a minor, but accepted him after three years.

Generations of his extended family gathered in the courtyard of their house in Qamishli town to recount his short life.

“I see him everywhere,” said his mother, Rojin Mohammed. “He left me with so many memories. He was so caring and loving.”

Walid was one of eight children and the youngest of the children. He can always walk around his mother.

“When he wanted something, he would come and kiss me,” she recalls. “And say ‘Can you pay me to buy cigarettes?'”

A young soldier was killed during days of fighting near a strategic dam – his body was found by his cousin who scouted the front lines. Through tears, his mother calls for revenge against IS.

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBC“They broke our hearts,” she says. “We buried many of our youth. May Daesh (IS) be completely destroyed,” she says. “I hope none of them are left.”

Instead, the Islamic State group has been recruiting and reorganizing — taking advantage of the security vacuum since the ouster of Syria’s longtime dictator Bashar al-Assad last December, according to Kurdish officials.

“Their attacks have increased 10-fold,” says Siyamend Ali, a spokesman for the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – a Kurdish militia that has been fighting IS for more than a decade and is the backbone of the SDF.

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBC“They took advantage of the chaos and got a lot of weapons from warehouses and depots (of the old regime).”

He says the militants have expanded their areas of operation and methods of attack. They have graduated from hit-and-run operations to attacking checkpoints and planting landmines.

His office walls are lined with photos of YPG members killed by IS.

For the US, YPG militias are an invaluable ally in the fight against terrorism. For Turkey, it is a terrorist group.

According to Ali, operations against IS have killed 30 YPG fighters and captured 95 IS militants over the past year.

Kurdish authorities have their hands – and jails – full with suspected IS fighters. Around 8,000 – from 48 countries including the UK, US, Russia and Australia – have been held in the North East prison network for years.

Whatever their guilt – or innocence – they were neither tried nor convicted.

The largest prison for IS suspects is Al-Sina in the city of Al Hasakah – surrounded by high walls and watch towers.

Through a small hatch in the cell door, we get a glimpse of the men who once terrorized nearly a third of Syria and Iraq.

Prisoners in brown uniforms – shaved – sit on opposite sides of the cell, silent and motionless on thin mattresses. Like the “caliphate” he declared in 2014, he looks thin, weak and defeated. Prison officials say the men were with IS until its last stand in the Syrian city of Baghouz in March 2019.

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBCSome detainees wear disposable masks to prevent the spread of infection. Tuberculosis is his companion in al-Sina, where he is kept indefinitely.

There is no TV or radio, no Internet or phone, and it is not known that Assad was ousted by Ahmed al-Shara, a former Islamist militant. At least that is the hope of the prison administration.

But according to the prison commander, who could not be identified for security reasons, IS is rebuilding itself behind bars. He says each wing of the prison has an emir, or leader, who issues fatwas – rulings on issues of Islamic law.

Leaders still have influence, he said. “And give orders and lessons in Sharia.”

One of the detainees, Hamza Parvez from London, agreed to speak to us as prison guards listened.

The former trainee accountant admitted to becoming an IS fighter at the age of 21 in early 2014. That made his citizenship expensive. When challenged about IS atrocities, including beheadings, he says many “unfortunate” things happened.

“A lot of things happened that I don’t agree with,” he said. “And there were things I agreed with. I wasn’t in charge. I was just a normal soldier.”

He says that now his life is in danger. “I’m on my deathbed… in a room full of tuberculosis,” he said. “I could die at any moment.”

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBCParvez is pleading to return to the UK after years in prison.

“I and the rest of the British citizens who are in prison here, we want no harm done to them,” he said. “We did what we did, yes. We came. We joined the Islamic State. This is something we cannot hide.”

I ask how people will accept that he is no longer a threat.

“They’ll have to take my word for it,” he says with a laugh.

“That’s something I can’t convince people of. They’re going to have to take a big risk to bring us back. It’s true.”

Britain, like many countries, is in no rush to do so.

As a result, the Kurds are holding about 34,000 fighters and their family members.

Women and children are arbitrarily detained in vast deserted tent camps that resemble open-air prisons. Human rights groups say it amounts to mass punishment – a war crime.

Rose Camp sits on the edge of the Syrian desert – whipped by the wind and scorched by the sun.

Mehek Aslam from London is eager to escape. She comes to see us in the manager’s office – slightly veiled, with a mask over her face and limping. She says she was beaten by Kurdish forces a few years ago and wounded by a bullet.

After agreeing to an interview, she speaks at length.

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBCAslam says she came to Syria with her Bengali husband Shahan Chaudhary only to “bring help” and claims they earn a living by “baking cakes”. He is now in Al-Sina prison and they have both been stripped of their citizenship.

The mother of four denies joining IS but admits to bringing her children to its territory, where her eldest daughter was killed in an explosion.

“I lost her in Baghouz. It was an RPG (rocket-propelled grenade) or a small bomb. Her leg was broken and she was stabbed in the back. She died in my arms,” she says softly.

She told me that her children had developed health problems in the camp, including her youngest, eight years old. But she admitted turning down offers to return them to the UK. She says they didn’t want to go without her.

“Unfortunately, my children grew up in the camp,” she said. “They don’t know the outside world. My two children were born in Syria, they’ve never seen Britain, and going to a family that doesn’t know them would be very difficult. No mother should have to choose to be separated from her children.”

But I told her that she had made other choices like coming to the caliphate where IS was killing civilians, raping and enslaving Yazidi women, and throwing people off buildings.

“I didn’t know about the Yazidi thing at the time, or people being thrown off buildings. We didn’t see any of that. We knew they were very extreme,” she said.

She said she was at risk in the camp because she knew she wanted to return to Britain.

“I’ve already been targeted as an apostate, and it’s in my community. My kids are stoned at school.”

I asked if she would like to return to the IS caliphate.

“Sometimes things go awry,” she said. “I don’t believe what we saw was a true representation in the Islamic language.”

After an hour-long interview, she returned to her tent without giving any indication that she would leave the camp.

The camp manager, Hekmiah Ibrahim, says there are nine British families in Rose – 12 of them with children. And, she adds, 75% of people in the camp still adhere to IS’s ideology.

There are worse places than Rose.

The atmosphere is very tense in al-Hol – a more radical camp where about 6,000 foreigners are being held.

We were given an armed escort to go to their section of the camp.

As we entered – carefully – the sound of banging echoed through the area. The guards said that outsiders had come and warned us that we might be attacked.

Gokte Coralton/BBC

Gokte Coralton/BBCVeiled women – clad head to toe in black – soon gathered. One answered my questions by running a finger across her neck – as if slitting her throat.

Several young children raised their index fingers – a gesture traditionally associated with Muslim prayer but hijacked by IS. We kept our visit short.

The SDF is patrolling the area outside and around the camp.

We joined them – hitting the desert track.

“Sleeper cells are everywhere,” said one of the commanders.

In recent months, they have focused on trying to get children out of the camps, “trying to free the cubs of the caliphate”, he added. Most attempts are blocked, but not all.

A new generation is being raised – inside razor wire – inheriting the brutal legacy of IS.

“We are worried about the children,” Hekmiah Ibrahim said back at the Rose camp.

“We’re sad to see them grow up in this swamp and embrace this ideology.”

Because of his early instincts, he believes he will be more radical than his father.

“They are the seeds of a new version of IS,” she said. “More powerful than the last one.”

Additional reporting by Wietske Burema, Goktay Koraltan and Fahad Fattah

Post Comment