South Korean fishermen are dying. Is climate change responsible?

Jean MackenzieSeoul Correspondent

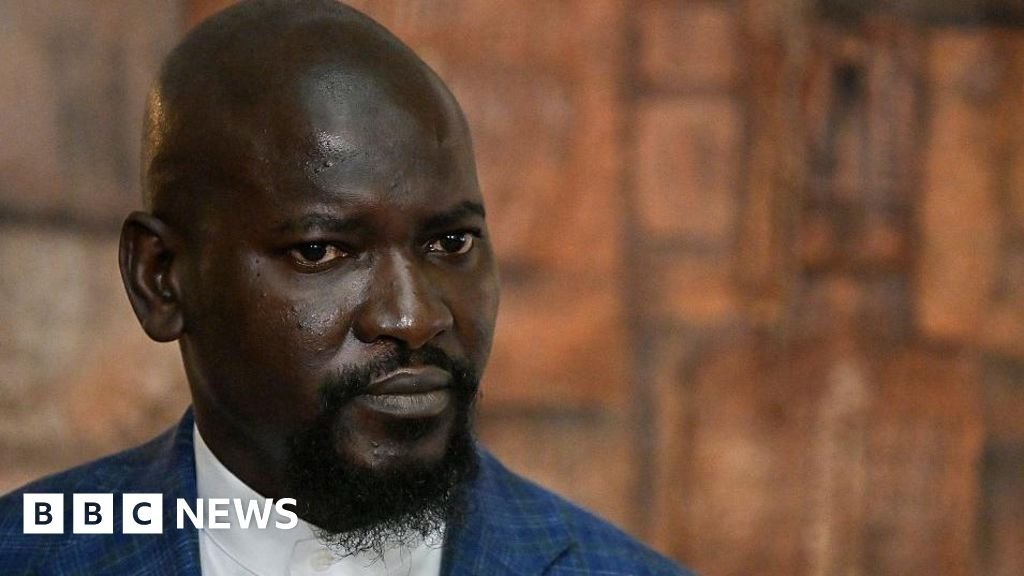

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeHong Suk-hui was waiting on the shores of South Korea’s Jeju Island when the call came. Their fishing boat had capsized.

Just two days earlier, the ship had anticipated a long and fruitful voyage. But as the winds grew stronger, his captain was ordered to turn back. On the way to port, a powerful wave hit from two directions and created a whirlpool and capsized the boat. Five of the 10 crew members, who were sleeping in their cabins below deck, drowned.

“When I heard the news, I felt like the sky was falling,” Mr Hong said.

Last year, 164 people were killed or missing in sea accidents around South Korea – a 75% jump from the previous year. Most were fishermen whose boats sank or capsized.

“The weather has changed, it’s getting windier every year,” said Mr. Hong, who is president of the Jeju Fishing Boat Owners Association.

“Whirlwinds pop up suddenly. We fishermen are convinced it’s brought down by climate change.”

South Korean Coast Guard

South Korean Coast GuardAlarmed by the rise in deaths, the South Korean government launched an investigation into the accidents.

This year, the head of the taskforce pointed to climate change as a major cause, while also highlighting other issues – the country’s aging fishing workforce, increasing dependence on migrant workers and poor safety training.

The seas around Korea are warming faster than the global average, in part because they are shallow. Between 1968 and 2024, the country’s average sea surface temperature rose by 1.58C, double the global increase of 0.74C.

Warmer waters are causing extreme ocean weather, creating conditions for tropical storms, such as typhoons, to become more intense.

They are prompting the migration of some fish species around South Korea, according to the country’s National Institute of Fisheries Science, forcing fishermen to travel farther and take greater risks to catch enough to survive.

Environmental campaigners say urgent action is needed to “stop the tragedy in Korean waters”.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeOn a rainy June morning, Jeju Island’s main harbor was full of fishing boats. Crews hurried between sea and land, refueling and stocking up for their onward journey, while boat owners anxiously paced the dockside making final preparations.

“I’m always afraid that something might happen to the boat, the risk is too high,” said owner Kim Seung-hwan, 54. “Winds have become more unpredictable and extremely dangerous.”

A few years ago, Mr. Kim noticed that the popular silver hairtail fish he depended on were disappearing from local waters and that his income had been cut in half.

Now his crew must travel deeper, more dangerous waters to find them, sometimes as far south as Taiwan.

“Because we operate so far away, it’s not always possible to get back quickly when there’s a storm warning,” he said. “It would be safer if we stayed closer to the coast, but we have to move away to make a living.”

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeProfessor Gug Seung-gi led an investigation into the recent accidents, which found that South Korea’s seas have become more dangerous. The number of marine weather warnings around the Korean Peninsula – warning fishermen of storms, storms and typhoons – increased by 65% between 2020 and 2024.

“Unpredictable weather is causing more boats to sink, especially smaller fishing vessels that are going further and are not built for such long, rough voyages,” he told the BBC.

Professor Kim Baek-min, a meteorologist at South Korea’s Pukyong National University, said that although climate change is increasing the likelihood of strong, sudden gusts of wind, a clear trend has yet to be established – more research and long-term data are needed.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeOn a foggy morning, we left the coast in the dark on a small trawler with Captain Park Hyung-il, who has been fishing off the south coast of Korea for more than 25 years. Determined to be upbeat, he sang Peace in the Sea. But as he approached the nets he had left overnight, his mood soured.

Anchovies were rarely seen among swarms of jellyfish and other foragers when he wound them up. After separating the anchovies, they only filled two boxes.

“Earlier, we used to fill 50 to 100 of these baskets in a day,” he said. “But this year the anchovies are gone and we’re catching more jellyfish than fish.”

Thousands of fishermen are facing disaster along the coast of South Korea. Over the past 10 years, the annual amount of squid caught in South Korean waters has fallen by 92%, while the anchovy catch has declined by 46%.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeHe said the anchovies caught by the park were also not marketable and must be sold as animal feed.

“This trip is basically worthless,” he sighed, explaining that it would only cover the day’s fuel costs, let alone his crew’s wages.

“The sea is a mess, nothing makes sense anymore,” Park continued. “I used to love this job. It was nice to know that somewhere in the country someone was eating the fish I caught. But now, with nothing to catch, that sense of pride is fading.”

And, with the means of livelihood disappearing, the youth no longer want to join the industry. In 2023, nearly half of South Korea’s fishermen will be over 65, down from less than a third a decade ago.

Increasingly, older captains must rely on the help of migrant workers from Vietnam and Indonesia. Often these workers do not receive adequate safety training and language barriers mean they cannot communicate with captains – further increasing the risks.

Woojin Chung, South Korea chief representative of the UK-based Environmental Justice Foundation, described it as “a vicious and tragic cycle”.

When you combine more extreme weather with the pressure to travel further, increased fuel costs and the need to rely on cheap, untrained foreign labour, “you’re more likely to face disaster”, she explained.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeOn February 9 this year, a large shipping trawler suddenly sank near the coastal city of Yeosu, killing 10 crew members. It was a bitterly cold, windy day and small boats were forbidden to go out, but this trawler was strong enough to withstand the gale. Why it fell down is still a mystery.

One of those killed is 63-year-old Young-mook. A fisherman for 40 years, he was thinking of retiring, but that morning someone called and asked him to fill a last-minute opening on a boat.

“It was so cold that once you got into it you couldn’t survive hypothermia, especially at his age,” said his daughter Ean, still reeling from his death.

Ein thinks it has become too easy for boat owners to blame climate change for accidents. Even in situations where bad weather plays a role, she believes it is the owners’ responsibility to assess the risks and keep their crew safe. “Ultimately it’s their call when to go out,” she said.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeAs a child, she remembers her father’s fridge being full of crabs and squid. “Now the stocks are gone, but the companies still force them out, and these men have worked as fishermen all their lives, they have no alternative job options, so they fish even when they are very weak,” she said.

EN wants owners to better maintain their boats, which are old. “Companies have insurance, so they get compensation after a boat sinks, but our loved ones can’t be replaced.”

Realizing that they cannot control the weather, officials are now working with fishermen to make their boats safer. We were with Mr Hong, whose boat capsized earlier this year, when a team of government inspectors came to carry out on-the-spot checks on two of his other vessels.

A government task force is recommending that boats be fitted with safety ladders, fishermen be required to wear life jackets and safety training be mandatory for all foreign crew. It also wants to improve search and rescue operations and give fishermen access to more localized and real-time weather updates.

Some regions are offering to pay fishermen to catch jellyfish to try to clean up the ocean, while squid fishermen are being offered loans to save them from bankruptcy and encourage them to retire.

BBC/Hosu Lee

BBC/Hosu LeeBecause the problem is likely to increase. Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN If carbon emissions and global warming continue on their current path, South Korea’s total fish catch is projected to decline by nearly a third by the end of this century.

“The future looks very bleak,” said anchovy fisherman Captain Park, now in his late 40s. He recently started a YouTube channel documenting his catches in hopes of making some extra cash. Park is the third generation of his family to work, and likely the last.

“It felt romantic to get up early and go to the sea. There was a sense of adventure and reward.”

“It’s really hard these days.”

Additional reporting by Hosu Lee and Leehyun Choi

Post Comment